Air pollution can vary sharply from place to place, both over a city and an entire continent. A busy intersection, a sheltered street canyon, an urban park, or areas downwind of industry can all experience very different levels of pollution than a monitoring station only a few kilometres away. Official air quality monitoring stations provide highly reliable measurements, but they are often too far apart to capture these fine-scale patterns. Citizen science can bridge this gap: Many thousands of people worldwide host low-cost sensors that measure fine particulate matter (PM2.5) where they live, work, and commute. The challenge is turning this information into continuous maps of air quality with high accuracy. Low-cost sensors differ in performance, siting, and maintenance, so their raw data cannot simply be interpolated to a map.

In CitiObs, we tackle this by combining two ideas: (1) rigorous quality control for citizen sensor data and (2) machine-learning fusion that blends trusted observations, models, satellites, sensor observations, and weather information to create value-added PM2.5 maps at 1 km resolution.

The first step is making citizen measurements analysis-ready. CitiObs developed the FILTER approach, built around a processing chain designed to harmonise and quality-check low-cost sensor time series at scale. In practice, this means systematically screening for issues like unrealistic values, stuck sensors (flatlines), and spatio-temporal inconsistencies, and then keeping only measurements that pass strict quality criteria. For our PM2.5 mapping work we used quality-controlled data from large citizen networks (including Sensor.Community and PurpleAir), focusing on the highest-quality subset so that the model learns from real signal rather than sensor artefacts.

The second step is data integration. Our mapping system S-MESH is a machine-learning framework that learns how PM2.5 behaves in space and time by combining many “clues” about pollution: chemical transport model forecasts, satellite aerosol information, meteorology, and land-surface characteristics along with ground observations. All inputs are aligned on the same 1 km grid. Traditionally, S-MESH is trained only using reference-grade station data for training and evaluation, so the final maps remain consistent with the best-available measurement standard.

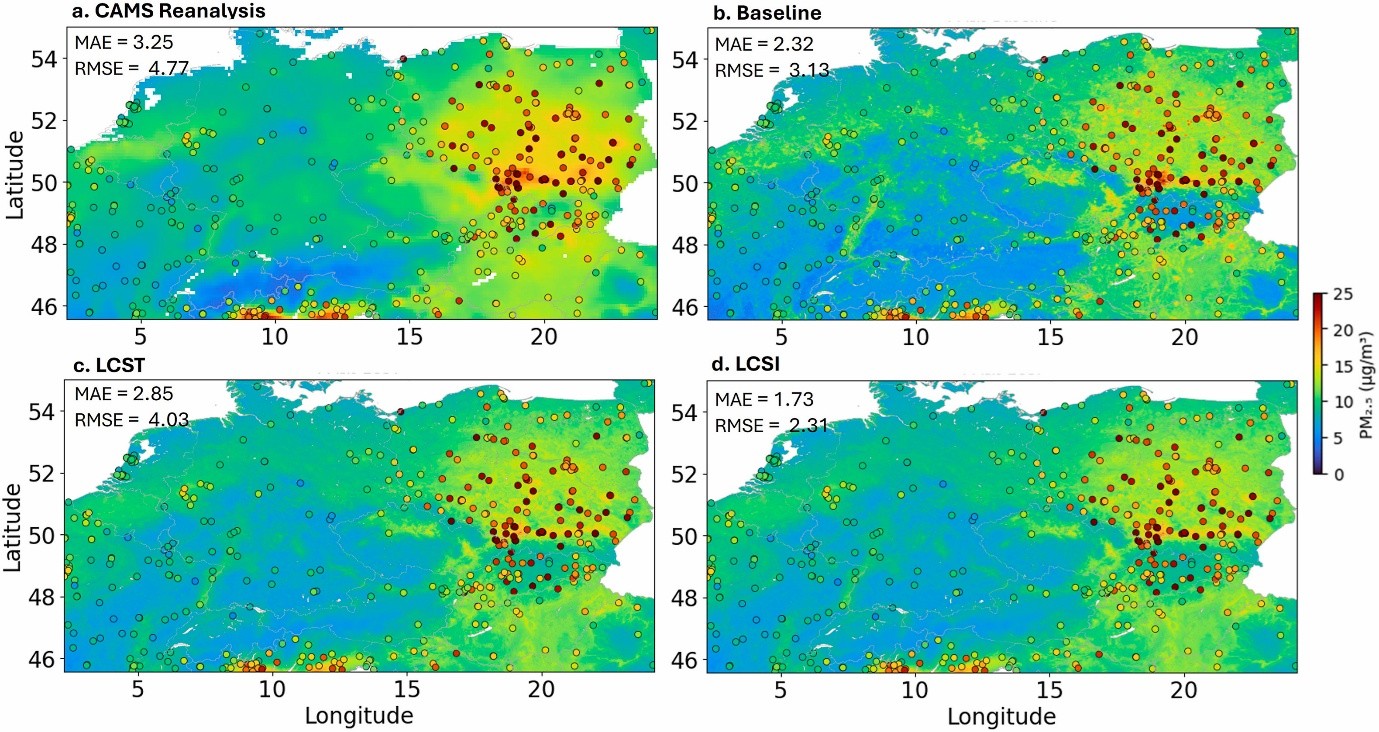

A key question we tested is how citizen sensors should enter a machine-learning mapping pipeline. In addition to a baseline S-MESH model without any sensor data, we evaluated two strategies over Central Europe (where citizen sensor density is high): 1) a model trained directly on low-cost sensor PM2.5 as the target and 2) a model using the regulatory stations as the target but with citizen sensors as an additional input variable. The second approach turned out to be the most effective and significantly improved the mapping accuracy. Instead of asking the model to treat low-cost sensors as “ground truth,” we let them inform local spatial detail through a distance-weighted field of citizen-provided PM2.5 and the distance to the nearest sensor. This helps the model learn where citizen information is strong and where it is absent, while still learning the overall calibration from official stations.

What did we gain? In sensor-dense areas, adding citizen observations as inputs improved agreement with independent reference stations and, just as importantly, produced richer local structure. The results showed sharper neighbourhood gradients and clearer hotspots during pollution episodes. In other words, citizen sensors helped the model “see” intra-urban variability that a sparse station network can miss. But we also learned where this approach can struggle. Since sensors are typically distributed very unevenly and for the most part clustered in cities, their influence on the map decreases quickly as one moves away from them. Far from sensors, the maps naturally revert toward what the baseline approach can infer from models, satellites, and meteorology. During large-scale transport events, uneven coverage can also make it harder to represent broad pollution plumes consistently between hotspots. These limitations are not a reason to dismiss citizen data. Rather, they underline why careful quality control, smart model design, and transparency about where the map is well supported are essential.

The main takeaway from the mapping activities in CitiObs is that community-based PM2.5 sensor networks can measurably improve air-quality maps when (a) data are quality-controlled and (b) the model uses them in a way that respects their uncertainties and spatial coverage. Done well, they don’t replace official monitoring but they complement it, filling in spatial detail and making air-quality information more locally relevant for communities and city decision-makers. Expanding these networks more evenly across Europe, and particularly into areas where there are gaps today, would likely strengthen mapping quality even further.

Further information can be found in

Shetty, S., Hassani, A., Hamer, P. D., Stebel, K., Salamalikis, V., Berntsen, T. K., Castell, N., and Schneider, P.: Evaluating the role of low-cost sensors in machine learning based European PM2.5 monitoring, Environmental Research, 291, 123558, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2025.123558, 2026.

Annual Average PM2.5 levels for 2021 from a) CAMS regional interim reanalysis, b) baseline, c) low-cost sensor as target (LCST), and d) low-cost-sensor as input (LCSI), overlaid with annual averages from station observations on the same color scale. Corresponding MAE and RMSE in μg/m3 for annual estimates from different models are reported.